Hungry for VR/AR

How designers can harness technology’s long reach to provoke viewer empathy and thoughtful immersion.

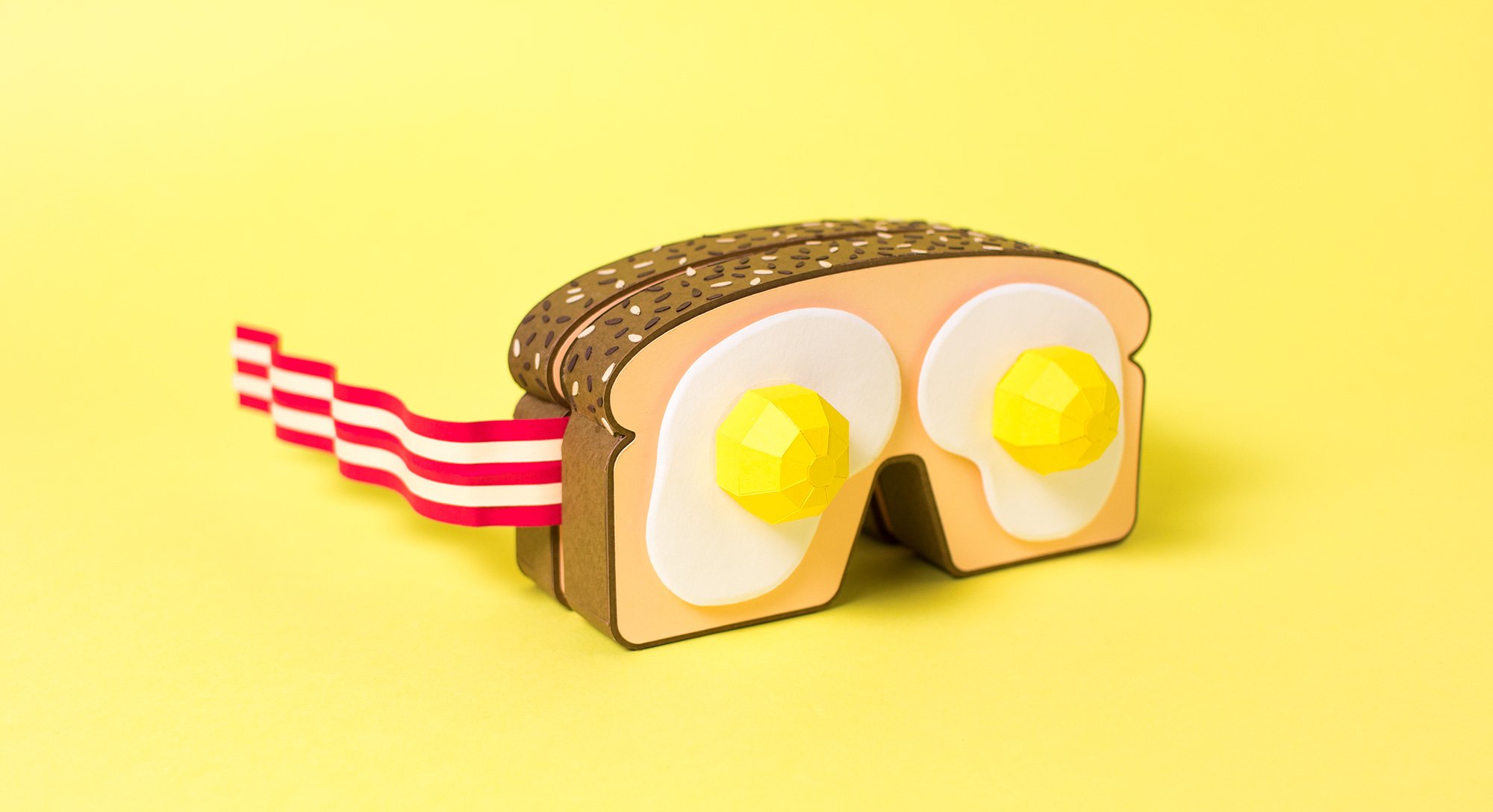

Image by Tommy Perez for Tim Lampe’s Morgenmete

For my thirtieth birthday, I received the gift of perspective. This manifested itself as a clunky pair of blacked out goggles strapped tentatively around my head. My tech-savvy brother mapped an invisible 6 x 9' boundary like a modern Harold and the Purple Crayon, gave me two ergonomic squirt guns with no barrel, and plunged me into the most immersive technological experience of my life. Let me preface this experience with the following: I am an empath. My feelings are already boundless. Strapped into a virtual word, I felt vulnerable, a floating entity in the dark.

Unlike early programmer-facing versions of VR where the viewer was restricted to head movements, I had reign of my living room rug. I could approach and retract from the narrative playing out in front of me. A reformed gamer, I understand the immersive power of world building. However, I learned I likely have agoraphobia, almost taking off the headset several times because I felt fearfully lost in an otherwise placid space scene. I literally squealed for an hour, twisting into a pretzel while spraying lettering in a world without gravity constraints, half lives, or relative scale. Sadly no footage exists to support my recollection, though we all laugh about it now. As graphic elements and noise swirled around me, I observed a radically different side of design than I’d previously experienced: proximity as closeness. And I was hooked.

Notable AR VR Articles:

For years, proximity in the arts has meant distance. Don’t touch. Keep behind the security line. The principle of Gestalt is a theory of unity concerning space between objects, how far apart items can be while feeling related. Distance regularly separates us from the most interesting parts of creative work, whether by design or otherwise. This barrier is an occupational hazard for industries like architecture; the most interesting features are often stories above or below, too removed to grasp without standing back at a distance. Watch children in a museum’s courtyard and the argument is made: docents chase kids off the lawns, reminding them there’s a difference between playground equipment and sculpture. Proximity is a luxury afforded to the maker; they get to experience closeness because they possess the work, will treat it reverently as it matures. Despite the physical presence of my own work, I’m the only one who lays hands on the project because everyone else is afraid to ruin what I’ve done. The barrier of entry is a lens, a screen, or a thin layer of oxidized dairy.

VR will change this. Finally an art form that can press the disembodied viewer, draw closer than their perceived skin. Color and sound, common elements, can challenge a person’s place in the universe, extract them briefly from their reality. Size becomes relative as illustrations quickly shift from massive and encroaching to tiny and self contained. The digital world, often austere and theoretical, is isolating to many, but VR is slowly teaching audiences to expect more. Museums are already scrambling to implement these changes because we’ve learned a shocking thing: virtual immersion can move the immovable among us. Coupled with thoughtful stories, we can create a cinematic moment that motivates viewers in a way print or video cannot. If someone with a staunch policy against immigration could virtually stand in a cataclysmic Syrian street as bombs spray overhead, they may leave the experience questioning their views.

What does this mean? We can feel more profoundly than ever before.

No technology is as elegant as it is effective at the onset. VR is the pager of immersive technology: expensive, individualized, painfully uncool to wear. However, its presence in the periphery pulls on the analog world. Installation exhibits have grown in popularity since mid-2016 in direct response to tech advancement. People crave more thoughtful, emotional engagement than ever before. Former warehouses become bastions of ice cream, worlds of color, and they’re just getting started. These highly curated spaces make for incredible selfies but also edit harsh environment into honed experiences for taste, touch, smell. I’ve seen a direct increase in installation and live demo requests in the last couple years. The correlation is clear: audiences want limitlessness despite clear limits.

Artists and designers tend to shrink at the introduction of new technology. I speak from experience, often wondering how x device will impact my outputs, raise the bar, add steps to my already complicated process. However, the sooner visual artists adapt this technology, the sooner they can evolve. AR is a baby step towards total integration, allowing digital magic to enter an already preexisting space. Pokémon Go has literally moved the masses to explore their neighborhoods on foot, sometimes with dark ramifications, but as a whole changing human engagement with their well known environments. Right now AR graphics challenge rather than compliment reality; they push against organic shapes with harsh colors and digitized angles. This is a mark of novelty. Sophisticated integration will be barely distinguishable from the preexisting environment. Dimensional, analog work like mine, those fluent in sculpture, set design, and natural textures like fur or silk will push the integration forward with the real life magic they already produce. People in these disciplines regularly grapple with spacial intelligence, forced perspective. Coupled with the technical knowledge and curiosity, those of us working in analog spaces are small steps from a collaborative leap. Stepping into new tech allows us to lead development and co-author the rules.

The most common uses thus far rely on transparency and light mapping to achieve large scale immersions. The work of Craig Winslow, his partnership with Gemma O’Brien are fine examples. However, AR proximity can find a home in intimate, small spaces. This is a largely untapped space, one I’ve seen most utilized in galleries; the work of Cyril Vouilloz aka Rylsee and Alexis Taieb aka TYRSA support this exploration. Natively digital work already stand a better chance of acclimating. 3D modelers, animators, and vector illustrators are obvious, but there is equal possibility for those like myself of a dimensional, analog space. Who better to grasp spatial challenges than those doing so every project? There is room to think broadly across invisible planes, to touch viewers in their native homes and lives. If we’re willing, we can fill these places with anything we can imagine.

I am looking for partners in the AR/VR industry. If you live in these experimental spaces and want to work together, please contact me.